XSP, Taglibs and Pipelines

In the first article in this series, we saw how to install, configure and test AxKit, and we took a look at a simple processing pipeline. In this article, we will see how to write a simple 10-line XSP taglib and use it in a pipeline along with XSLT to build dynamic pages in such a way that gets the systems architects and coders out of the content maintenance business. Along the way, we’ll discuss the pipeline processing model that makes AxKit so powerful.

First though, let us catch up on some changes in the AxKit world.

CHANGES

Matt and company have released AxKit v1.5.1, and 1.5.2 looks as though it will be out soon. 1.5.1 provides a few improvements and bug fixes, especially in the XSP engine discussed in this article. The biggest additions are the inclusion of a set of demonstration pages that can be used to test and experiment with AxKit’s capabilities, and another module to help with writing taglibs (Jorge Walter’s SimpleTaglib, which we’ll look at in the next article).

There has also been a release policy change: The main AxKit distributions (AxKit-1.5.1.tar.gz for instance) will no longer contain the minimal set of prerequisites; these will now be bundled in a separate tarball. This policy change enables people to download just AxKit (when upgrading it, for instance) and recognizes the fact that AxKit is an Apache project while the prerequisites aren’t. Until the prerequisite tarball gets released, the source tarball that accompanies this article contains them all (though it installs them in a local directory only, for testing purposes). The main AxKit tarball still includes all the core AxKit modules.

XSP and taglibs

We touched on eXtensible Server Pages and taglibs in the last article; this time we’ll take a deeper look and try to see how XSP, taglibs and XSLT can be combined in a powerful and useful way.

A quick taglib refresher: A taglib is a collection of XML tags in an XML namespace that act like conditionals or subroutine calls. Essentially, taglibs are a way of encoding logic and dynamic content in to pages without including raw “native” code (Perl, Java, COBOL; any of the popular Web programming languages) in the page; each taglib provides a set of related services and multiple taglibs may be used in the same XSP page.

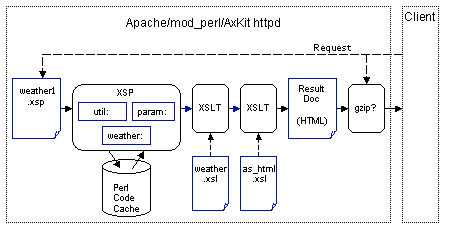

For our example, we will build a “data driven” processing pipeline (clicking on a blue icon or arrow will take you to the relevant documentation or section of this article):

NOTE: A little icon like this will be shown with the description of each piece of the pipeline with that piece hilighted. Clicking on those icons will bring you back to this diagram.

This pipeline has five stages:

- the XSP document (

weather1.xsp) defines what chunks of raw data (current time and weather readings) are needed for this page in a simple XML format, - the XSP processor applies taglibs to assemble the raw data for the page,

- the first XSLT processor and stylesheet (

weather.xsl) format the raw data in to usable content, - the second XSLT processor and stylesheet (

as_html.xsl) lays out and generates the final page (“Result Doc”), and - the Gzip compressor automatically compresses the output if the client can comprehend compressed content (even when an older browser is bashful and does not announce that it can cope with gzip-encoded content).

This multipass approach mimics those found in real applications; each stage has a specific purpose and can be designed and tested independently of the others.

In a real application, there might well be more filters: Our second XSLT filter might be tweaked to build document without any “look and feel,” and an additional filter could be used to implement the “look and feel” of the presentation after the layout is complete. This would allow look and feel to be altered independently of the layout.

We call this a “data driven” pipeline because the document feeding the pipeline defines what data is needed to serve the page; it does not actually contain any content. Later stages add the content and format it. We’ll look at a “document driven” pipeline, which feeds the pipeline with the document to be served, in the next article.

Why pipelines?

The XML pipeline-processing model used by AxKit is a powerful approach that brings technical and social advantages to document-processing systems lsuch as Web applications.

On the social side, the concept of a pipeline or assembly line is simple enough to be taught to and grasped by nonprogrammers. Some of the approaches used by HTML-oriented tools (like many on CPAN) are not exactly designer-friendly: They rely on programmer-friendly concepts such as abstract data structures, miniature programming languages, “catch-all” pages and object-oriented techniques such as method dispatch. To be fair, some designers can and do learn the concepts, and others have Perl implementors who deploy these tools in simple patterns that are readily grasped.

The reason that HTML-oriented tools have a hard time something as simple as a pipeline model is that HTML is a presentation language and does not lend itself to describing data structures or to incremental processing. The advantage of incremental processing is that the number of stages can be designed to fit the application and organization; with other tools, there’s often a one- or two-stage approach where the first stage is almost entirely in the realm of the Perl coders (“prepare thedata”) and the second is halfway in the realm of the coders and halfway in the designer’s realm.

XML can be used both to describe data structures and mark up prose documents; this allows a pipeline to mingle data and prose in flexible ways. Each processing stage is XML-in, XML-out (except for the first and last, which often consume and generate other formats). However, the stages aren’t limited to dealing purely with XML: The taglibs we’re using show one way that stages can use Perl code (and, by extension, many other languages; see the Inline series of modules), external libraries, and almost any non-XML data as needed. Not only does My::WeatherTaglib integrate with Perl code, it’s also requesting data over the Internet from a remote site.

The use of XML as the carrier for data between the stages also allows each stage to be debugged and unit tested. The documents that forwarded between the stages are often passed as internal data structures instead of XML strings for efficiency’s sake, but they can be rendered (like the examples shown in this article) and examined, both for teaching purposes and debugging purposes. The uniform look and feel of XML, whatever it’s disadvantages, is at least readily understood by any competent Web designer.

Pipelines are also handy mechanisms in that the individual stages are chosen at request time; different stages can be selected to deliver different views of the same content. AxKit provides several powerful mechanisms for configuring pipelines, the <xml-stylesheet ...> approach used in this article is merely the simplest; future articles will explore building flexible pipelines.

Pipelines also make a useful distinction between the manager (AxKit) and the processing technologies. Not only does this allow you to mix and match processing techniques as needed (AxKit ships with nine “Languages”, or types of XML processor, and several “Providers”, or data sources), it also allows new technologies to be incorporated in to existing sites when a new technology is needed.

Moreover, technologies like XML and XSLT are standardized and are becoming widely accepted and supported. This means that most, if not all the documents in our example pipeline can be handed off to non-Perl coders without (much) fear of them mangling the code. When they do mangle it; tools such as xsltproc (shipped with libxslt, one of the AxKit XSLT processors) can be used to give the designers a first line of defense before calling in the programmers. Even taglibs, nonstandard though they are, leverage the XML standard to make logic and data available to noncoders in a (relatively) safe manner. For instance, here’s an excellent online tutorial provided by ZVON.org.

Mind you, XML and XSLT have their rough spots; the trick is that you don’t need to know all the quirky ins and outs of the XML specification or use XSLT for things that are painful to do in it. I mean, really, when was the last time you dealt with a notation declaration? Most uses of XML use a small subset of the XML specification, and other tools such as XSP, XPathScript and various schema languages can be used where XSLT would only make the problem more difficult.

What stages are appropriate depends on the application’s requirements and those of the organization(s) involved in building, operating and maintaining it. In the next article, we’ll examine a “document driven” pipeline and a taglib better suited for this approach that uses different stages.

All that being said there will always be a place for the non-XML and non-pipelined solutions: XML and pipelines are not panaceas. I still use other solutions when the applications or organizations I work with would not benefit from XML.

httpd.conf: the AxKit configuration

Before we start in to the example code, let’s glance at the AxKit configuration. Feel free to skip ahead to the code if you like; otherwise, here’s the configuration we’ll use in httpd.conf:

## ## Init the httpd to use our “private install” libraries ## PerlRequire startup.pl

##

## AxKit Configuration

##

PerlModule AxKit

<Directory /home/me/htdocs">

Options -All +Indexes +FollowSymLinks

# Tell mod_dir to translate / to /index.xml or /index.xsp

DirectoryIndex index.xml index.xsp

AddHandler axkit .xml .xsp

AxDebugLevel 10

AxGzipOutput Off

AxAddXSPTaglib AxKit::XSP::Util

AxAddXSPTaglib AxKit::XSP::Param

AxAddXSPTaglib My::WeatherTaglib

AxAddStyleMap application/x-xsp

Apache::AxKit::Language::XSP

AxAddStyleMap text/xsl

Apache::AxKit::Language::LibXSLT

</Directory>

This is the same configuration from the the last article—most of the directives and the processing model used by Apache and AxKit for them are described in detail there. The two directives in bold have been added. The key directives for our example are AxAddXSPTaglib and AxAddStyleMap.

The AxAddXSPTaglib directives load three tag libraries: Kip Hampton’s Util and Param taglibs and our very own WeatherTaglib. Util will allow our example to get at the system time; Param will allow it to parse URLs; and WeatherTaglib will allow us to fetch the current weather conditions for that zip code.

The two AxAddStyleMap directives map a pair of mime types to an XSP and an XSLT processor. Our example source document will refer to these mime types to configure instances of XSP and XSLT processors in to the processing pipeline.

We’re using Apache::AxKit::Language::LibXSLT to perform XSLT transforms, which uses the GNOME project’s libxslt library under the hood. Different XSLT engines offer different sets of features. If you prefer, then you can also use Apache::AxKit::Language::Sablot for XSLT work. You can even use them in the same pipeline by assigning them to different mime types.

My::WeatherTaglib

My::WeatherTaglib

Here’s a taglib that uses Geo::Weather module on CPAN to take a zip code and fetch some weather observations from weather.com and convert them to XML:

package My::WeatherTaglib;

$NS = "http://slaysys.com/axkit_articles/weather/";

@EXPORT_TAGLIB = ( 'report($zip)' );

use strict;

use Apache::AxKit::Language::XSP::TaglibHelper;

use Geo::Weather;

sub report { Geo::Weather->new->get_weather( @_ ) }

1;

This taglib uses Steve Willer’s TaglibHelper (included with AxKit) to automate the drudgery of dealing with XML. Because of this, our example taglib distills a lot of power into a few lines of Perl. Don’t be fooled, though, there’s a lot going on behind the curtains with this module.

When a tag like <weather:report zip="15206"/> is encountered in an XSP page, it will be translated into a call to report( "15206" ), the result of the call will be converted to XML and will replace the original tag in the XSP output document.

The $NS variable sets the namespace URI for the taglib; this configures XSP to direct all elements within the namespace http://slaysys.com/axkit_articles/weather/ to My::WeatherTaglib, as we’ll see in a bit.

When used in an XSP page, all XML elements supplied by a taglib will have a namespace prefix. For instance, the prefix

weather:is mapped to My::WeatherTaglib’s namespace in the XSP page below. This prefix is not determined by the taglib&8212;we could have chosen another; this section assumes that the prefixweather:is used for the sake of clarity.

The @EXPORT_TAGLIB specifies what functions will be exported as elements in this namespace and what parameters they accept (see the documentation for details). The report($zip) export specification exports a tag that is invoked like <weather:report zip="..."/> or

<weather:report>

<weather:zip>15206</weather:zip>

</weather:report>

The words “report” and “zip” in the @TAGLIB_EXPORT definition are used to determine the taglib element and attribute names; the order of the parameters in the definition determines the order they are passed in to the function. When invoking a taglib, the XML may specify the parameters in any order in the XML. The names they are specified with are not important to or visible from the Perl code by default (see the *argument function specification for how to accept an XML tree if need be).

All that’s left for us to do is to write the “body” of the taglib by use()ing Geo::Weather and writing the report() subroutine.

There are two major conveniences provided by TaglibHelper. The first is welding Perl subroutines to XML tags (via the @EXPORT_TAGLIB definitions). The second is converting the Perl data structure returned by report(), a hash reference like

{

city => "Pittsburgh",

state => "PA",

cond => "Sunny",

temp => 76,

pic => "http://image.weather.com/web/common/wxicons/52/26.gif",

url => "http://www.weather.com/search/search?where=15206",

...

}

in to well balanced XML like:

<city>Pittsburgh</city>

<state>PA</state>

<cond>Sunny</cond>

<temp>76</temp>

<pic>http://image.weather.com/web/common/wxicons/52/26.gif</pic>

<url>http://www.weather.com/search/search?where=15206</url>

...

TaglibHelper allows plain strings, data structures and strings of well-balanced XML to be returned. By writing a single one-line subroutine that returns a Perl data structure, we’ve written a taglib that requires no Perl expertise to use (any XHTML jock could use it safely using their favorite XML, HTML or text editor) and that can be used to serve up “data” responses for XML-RPC-like applications or “text” documents for human consumption.

The Data::Dumper module that ships with Perl is a good way to peer inside the data structures floating around in a request. Wehn run in AxKit, a quick

warn Dumper( $foo );will dump the data structure referred to by$footo the Apache error log.

The output XML from a taglib replaces the orignal tag in the result document. In our case, the replacement XML is not too useful as-is, it’s just data that looks a bit XMLish. Representing data structures as XML may seem awkward to Perl gurus, but it’s quite helpful if you want to get the Perl code safely out of the way and allow others to use XML tools to work with the data.

The “data documents” from our XSP processor will upgraded in later processing stages to content that is presentable to the client; our XSP page neither knows nor cares how it is to be presented. Exporting the raw data as XML here is intended to show how to get the Perl gurus out of the critical path for content development by allowing site designers and content authors to do it.

Emitting structured data from XSP pages is just one approach. Taglibs can return whatever the “best fit” is for a given application, whether that be raw data, pieces of content or an entire article.

Cocoon, the system AxKit was primarily inspired by, uses a different approach to writing taglibs. AxKit also supports that approach, but it tends to be more awkward, so it will be examined in the next article. We’ll also look at Jorge Walter’s new SimpleTaglib module then, which is newer and more flexible, but less portable than the TaglibHelper module we’re looking at here.

weather1.xsp: Using My::WeatherTaglib

Here’s a page (weather1.xsp) that uses the My::WeatherTaglib and the “standard” XSP util taglib we used in the previous article:

<?xml-stylesheet href="NULL" type="application/x-xsp"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="weather.xsl" type="text/xsl" ?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="as_html.xsl" type="text/xsl" ?>

<xsp:page

xmlns:xsp="http://www.apache.org/1999/XSP/Core"

xmlns:util="http://apache.org/xsp/util/v1"

xmlns:param="http://axkit.org/NS/xsp/param/v1"

xmlns:weather="http://slaysys.com/axkit_articles/weather/"

>

<data>

<title><a name="title"/>My weather report</title>

<time>

<util:time format="%H:%M:%S" />

</time>

<weather>

<weather:report>

<!-- Get the ?zip=12345 from the URI and pass it

to the weather:report tag as a parameter -->

<weather:zip><param:zip/></weather:zip>

</weather:report>

</weather>

</data>

</xsp:page>

When weather1.xsp is requested, AxKit parses the <?xml-stylesheet ...?> processing instructions and uses the AxAddStyleMap directives to build the processing chain shown above.

The XSP processor is the first processor in the pipeline. As it parses the page, it sends all elements with util:, param: or weather: prefixes to the Util, Param, and WeatherTaglib taglibs. This mapping is defined by the xmlns:... attributes and by the namespace URIs that are hardcoded into each taglib’s implementation (see the $NS variable in My::WeatherTaglib).

In this page, the <util:time> element results in a call to Util’s get_date() and the value of the format= attribute is passed in as a parameter. The string returned by get_date() is converted to XML and emitted instead of the <util:time> element in the output page. This shows how to pass simple constant parameters to a taglib.

We’re getting slightly trickier with the <weather:report> element: This construct fetches the zip parameter from the request URI’s query string (or form field) and passes it to WeatherTaglib’s report() as the $zip parameter. Thanks to Kip Hampton for the help in using AxKit::XSP::Param in this manner.

Because we have the AxDebugLevel set to 10, you can see these calls the compiled version of weather1.xsp; the generated Perl code is written to Apache’s error log—usually $SERVER_ROOT/logs/error_log.

The <a name="title"/> in the <title> element is a contrivance put in this page to show off a feature later in the processing chain. Be glad it’s not the dreaded <blink> tag!

The XML document that is outputted from the XSP processor and fed to the first XSLT processor looks like (taglib output in bold):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<data>

<title><a name="title"/>My weather report</title>

<time>16:11:55</time>

<weather>

<state>PA</state>

<heat>N/A</heat>

<page>/search/search?where=15206</page>

<wind>From the Southwest at 10</wind>

<city>Pittsburgh</city>

<temp>76</temp>

<cond>Sunny</cond>

<uv>2</uv>

<visb>Unlimited</visb>

<url>http://www.weather.com/search/search?where=15206</url>

<dewp>53</dewp>

<zip>15206</zip>

<baro>29.75</baro>

<pic>http://image.weather.com/web/common/wxicons/52/26.gif</pic>

<humi>31</humi>

</weather>

</data>

This data is largely presentation-neutral—kindly overlook the U.S. centric temperature scale—it can be styled as needed.

To generate this intermediate document, just commenting out all but the first

<?xml-stylesheet ... ?>processing instruction and request the page like so:$ lynx -source localhost:8080/02/weather1.xsp?zip=15206 | xmllint --format -

xmllintis installed with the GNOMDElibxsmllibrary used by various parts of AxKit.When we cover how to build pipelines in more dynamic ways than using these stodgy old xml-stylesheet PIs, those techniques can be used to allow intermediate documents to be shown by varying the request URI.

weather.xsl: Converting Data to Content

Here’s how we can convert the data document emitted by the XSP processor into more human-readable text. As described above, we’re taking a two-step approach to simulate a “real-world” scenario of turning our data into chunks of content in one (reusable) step and then laying the HTML out in a second step.

weather.xsl is an XSLT stylesheet that uses several templates to convert the XSP output in to something more readable:

<xsl:stylesheet

version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

>

<xsl:template match="/data/time">

<time>Hi! It's <xsl:value-of select="/data/time" /></time>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="/data/weather">

<weather>The weather in

<xsl:value-of select="/data/weather/city" />,

<xsl:value-of select="/data/weather/state"/> is

<xsl:value-of select="/data/weather/cond" /> and

<xsl:value-of select="/data/weather/temp" />F

(courtesy of <a href="{/data/weather/url}">The

Weather Channel</a>).

</weather>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="@*|node()">

<!-- Copy the rest of the doc verbatim -->

<xsl:copy>

<xsl:apply-templates select="@*|node()"/>

</xsl:copy>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

This is applied by the first XSLT processor in the pipeline.

This is applied by the first XSLT processor in the pipeline.

The interesting thing here is that we are using two templates (shown in bold) to process different bits of the source XML. These templates “blurbify” the time and weather data in to presentable chunks and, as a side-effect, throw away unused data from the weather report.

The third template just passes the rest through (XSLT has some annoying qualities, one of which is that it takes a complex bit of code to simple pass things through “as is”). However, this is boilerplate&8212;right from the XSLT specification, in fact&8212;and need not interfere with designers creating the two templates we actually want in this stylesheet.

Another annoying quality is that XSLT contructs look visually similar to the templates themselves. This violates the language design principle “different things should look different,” which is used in Perl and many other languages. This can be ameliorated by using an XSLT-aware editor or syntax hilighting to make the differences between XSLT statements and “payload” XML clear.

The output from the first XSLT processor looks like (template output in bold):

The output from the first XSLT processor looks like (template output in bold):

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<data>

<title><a name="title"/>My weather report</title>

<time>Hi! It's 16:50:36</time>

<weather>The weather in

Pittsburgh,

PA is

Sunny and

76F

(courtesy of <a href="http://www.weather.com/search/search?where=15206">The

Weather Channel</a>)

</weather>

</data>

Now we have a set of chunks that can be placed on a Web page. This technique can be used to build sidebars, newspaper headlines, abstracts, contact lists, navigation cues, links, menus, etc., in a reusable fashion.

as_html.xsl: Laying out the page

The final step in this example is to insert the chunks we’ve built into a page of HTML using the as_html.xslstylesheet:

<xsl:stylesheet

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

version="1.0">

<xsl:output method="html" />

<xsl:template match="/">

<html>

<head>

<title><xsl:value-of select="/data/title" /></title>

</head>

<body>

<h1><xsl:copy-of select="/data/title/node()" /></h1>

<p ><xsl:copy-of select="/data/time/node()" /></p>

<p ><xsl:copy-of select="/data/weather/node()" /></p>

</body>

</html>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

<html>

<head>

<meta content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" http-equiv="Content-Type">

<title>My weather report</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1><a name="title"/>My weather report</h1>

<p>Hi! It's 17:05:08</p>

<p>The weather in

Pittsburgh,

PA is

Sunny and

76F

(courtesy of <a href="http://www.weather.com/search/search?where=15206">The

Weather Channel</a>).

</p>

</body>

</html>

Using the /data/title from the data document in two places in the result document is a minor example of the benefit of separating the original data generation from the final presentation. In the <title> element, we’re using xsl:value-of, which returns just the textual content; in the <h1> element, we’re using xsl:copy-of, which copies the tags and the text. This allows the title to contain markup that we strip in one place and use in another.

This is similar to the situation often found in real applications where things like menus, buttons, location tell-tales (“Home >> Articles >> Foo” and the like) and links to related pages often occur in multiple places. Widgets like these make ideal “chunks” that the layout page can place as needed.

This is only one example of a “final rendering” stage; different filters could be used instead to deliver different formats. For instance, we could use XSLT to deliver XML, XHTML, and/or plain text versions, or we could use an AxKit-specific processor, XPathScript, to convert to things like RTF, nroff, and miscellaneous documentation formats that XML would otherwise have a hard time delivering.

AxKit optimizes this two-stage XSLT processing by passing the internal representation used by

libxsltdirectly between the two stages. This means that output from one stage goes directly to the next stage without having to be reparsed.

Relating weather1.xsp to the real world

If you squint a little at the code in My::WeatherTaglib, then you can imagine using a DBI query instead of having Geo::Weather query a remote Web site (Geo::Weather is used instead of DBI in this article to keep the example code and tarball relatively simple).

Writing queries and other business logic in to taglibs has several major advantages:

- the XML taglib API puts a designer friendly face on the queries, allowing the XSP page to be tweaked or maintained by non-Perl literate folks with their preferred tools, hopefully getting you off the “please tweak the query parms” critical path.

- Since the taglib API is XML, standard XML editors will catch basic syntax errors without needing to call in the taglib maintainer.

- Schema validators and XSLT tools can also be used to allow the designers to check the higher-level syntax before pestering the taglib maintainer.

- The query parameters and output can be touched up with Perl, making the “high level” XML interface simpler and more idiot-proof.

- The output is XML, so other XML processors can be used to enhance the content and style. This allows, for instance, XSLT literate designers to work on the presentation without needing to learn or even see (and possibly corrupt) any Perl code or a new language (as is required with most HTML templating solutions).

- It’s quite difficult to accidently generate malformed XML using XSP: a well-formed XSP usually generates well-formed output.

- The queries are decoupled from the source XML, so they can be maintained without touching the XSP pages.

- The taglibs can be unit tested, unlike embedded code.

- Taglibs can be wrappers around existing modules, so the same Perl code can be shared by both the web front end and any other scripts or tools that need them.

- The plug-in nature of taglibs allows using many public and private XSP taglibs facilities for rapid prototyping. CPAN’s chock full of ’em.

- In addition to the “function” tags like the two demostrated above, you can program “conditional” tags that control whether or not a block of the XSP page is included; this gives you the ability to respond to user preferences or rights, for instance.

The DBI module lets you work with almost any database ranging from comma separated value files (with SQL JOIN support no less) through MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, etc, etc., and returns Perl data structures just crying out to be returned from a taglib function and turned in to XML.

For quick one-off pages and prototypes, the ESQL taglib allows you to embed SQL directly in XSP pages. This is not recommended practice because it’s not efficient enough for heavily trafficed sites (the database connection is rebuilt each time), and because mixing programming code in with the XML leads to some pretty unreadable and hard-to-maintain pages, but it is good for one-off pages and prototypes.

Help and thanks

In case of trouble, have a look at some of the helpful resources we listed last time.

Thanks to Kip Hampton, Jeremy Mates and Martin Oldfield, for their thorough reviews, though I’m sure I managed to sneak some bugs by them. AxKit and many of the Perl modules it uses are primarily written by Matt Sergeant with extensive contributions from these good folks and others, so many thanks to all contributors as well.

Copyright 2002, Robert Barrie Slaymaker, Jr. All Rights Reserved.

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub