The State of the Onion 10

Welcome to the tenth State of the Perl Onion. For those of you who are unfamiliar with my methods, this is the annual speech wherein I ramble on about various things that are only marginally related to the state of Perl. I’ve gotten pretty good at rambling in my old age.

In the Scientific American that just came out, there’s an article on chess experts, written by an expert, on what makes experts so expert. This expert claims that you can become an expert in just about anything if you study it persistently for ten years or so. So, since this is my tenth State of the Onion, maybe I’m about to become an expert in giving strange talks. One can only hope (not).

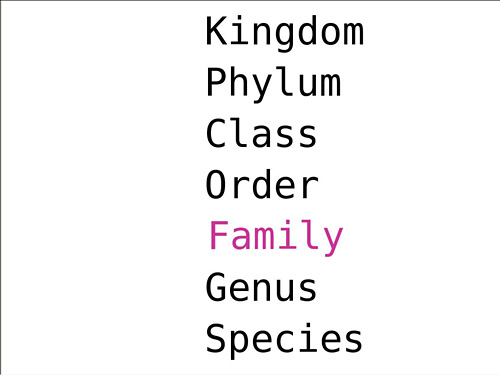

Speaking of chess, how many of you recognize this?

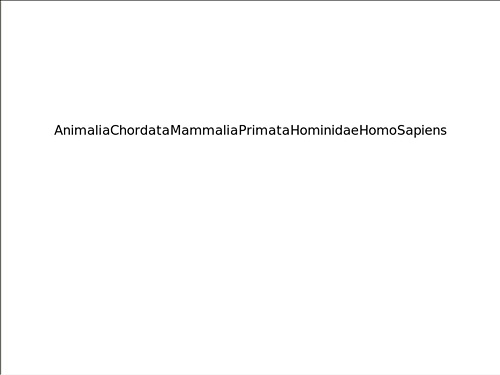

Does this help?

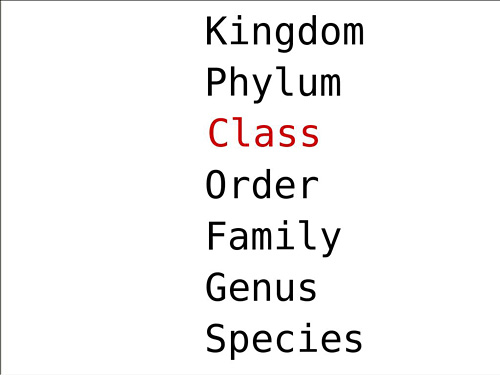

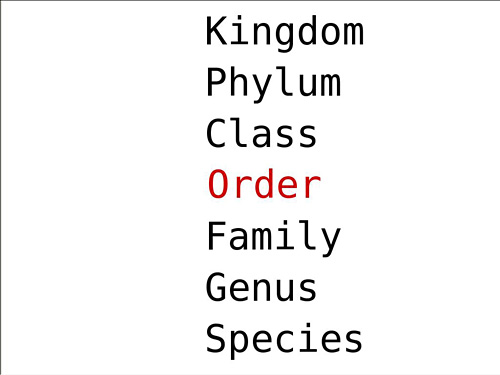

This is, of course, the mnemonic for the old Linnean taxonomy of biological classification.

Those of you who understand computers better than critters can think of these as nested namespaces.

This is all about describing nature, so naturally, different languages care about different levels.

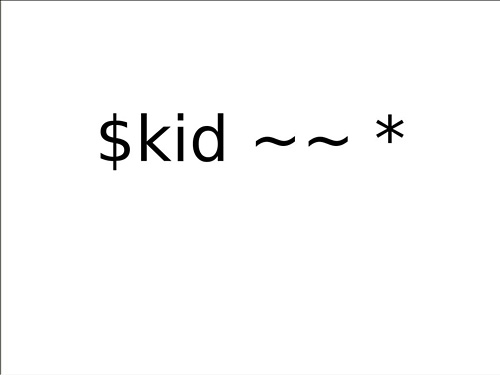

For instance, PHP isn’t much into taxonomy, so everything in PHP is just its own species in a flat namespace. Congratulations, this is your new species name:

Ruby, of course, is interested primarily in Classes.

Python, as the “anti-Perl,” is heavily invested in maintaining Order.

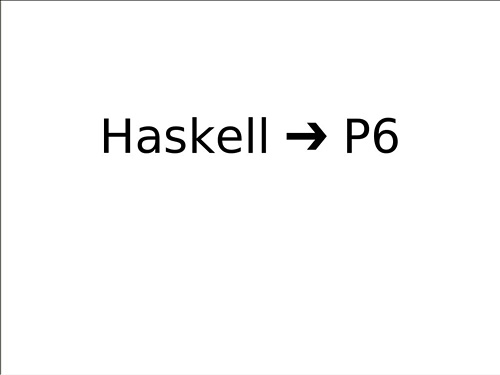

Now, you might be smart enough to program in Haskell if you’ve received a MacArthur Genus award.

… used to be I couldn’t spell “genus,” and now I are one …

Moving right along toward the other end of the spectrum, we have JavaScript that kind of believes in Phyla without believing in Classes.

And at the top of the heap, playing king of the mountain, we have languages like C# and Java. The kingdom of Java only has one species.

The kingdom of C# has many species, but they all look like C#.

Well, that leaves us with families.

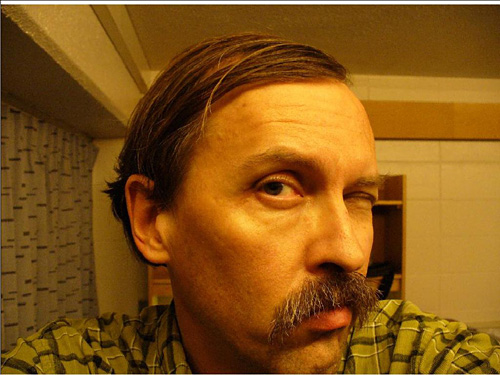

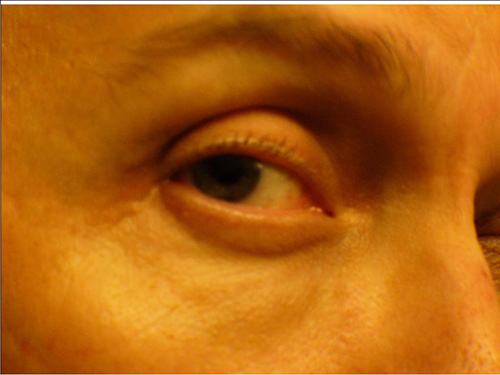

I expect I have a pretty good excuse for thinking a lot about families lately, and here is my excuse:

This is Julian, my grandson. Julian, meet the open source hackers. Open source hackers, meet Julian.

Many of you will remember my daughter Heidi from previous OSCONs. A couple years ago she married Andy, and Julian is the result. I think he’s a keeper. Julian, I mean.

Well, and Andy too.

Andy obviously has his priorities straight. I would certainly recommend him as a son-in-law to anyone. (Wait, that doesn’t quite work …)

There are many definitions of family, of course. Here’s a mommy and a daddy truck. They live on a truck farm, and raise little trucks.

Out in California, the word “family” keeps leaping out at me from various signs. People use the word “family” in some really weird ways.

There was a Family Fun Center, with a miniature golf course. I believe that sign. At least for the golf. As a parent, I’m not sure the game arcade is for the whole family. I’m an expert in staying out of loud places.

But the sign that said “Farmers Feed America–Family Water Alliance” … I suspect the word “family” is in there more for its PR value than anything else.

And, of course, “family planning” is for when you plan not to have a family. Go figure.

All of my kids were unplanned, but that doesn’t mean they were unwanted.

Many of you know that I have four kids, but in a strange way, I really have five, if you count Perl.

Geneva thinks of Perl as more or less her twin sister, since they were both born in 1987. But then, Geneva is strange.

Some people think Perl is strange too. That’s okay–all my kids are a little strange. They come by it naturally.

Here’s a self-portrait of the other end of Geneva.

Here’s what you usually see of Lewis.

Here’s some of Aron, pulling the door that says “push.”

And here’s Heidi.

She always was a pale child.

Actually, here’s the real picture.

You can see she’s actually quite sane. Compared to the rest of us.

Here’s a picture of my wife Gloria.

Here’s another picture of my wife. Well, her arms. The feet are my mom’s. Actually, this is really a picture of my granddog, Milo. He’s the one on the right.

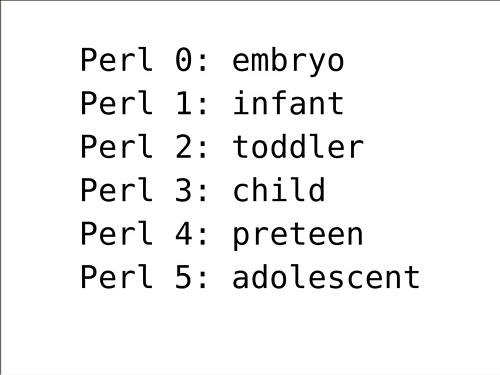

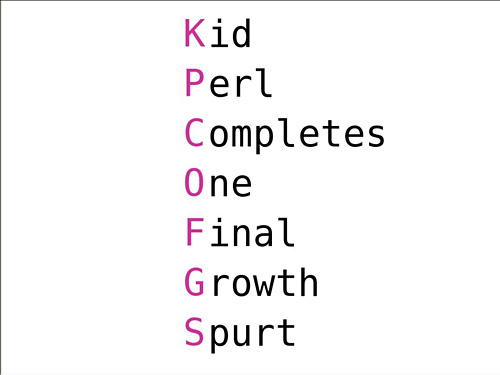

I’ve talked before about how the stages in Perl’s life are very much like that of a kid. To review:

This extended metaphor can be extended even further as necessary and prudent. Actually, it’s probably unnecessary and imprudent, but I’ll extend it anyway, because I find the metaphor useful. Perl, my fifth child, is showing various signs that she is about to grow up, and as a pseudo-parent, that makes me pseudo-proud of her. But there are other ways the metaphor makes me happy. For instance, it gives me another argument about the name of Perl 6.

From time to time, people have suggested that Perl 6 is sufficiently different from Perl 5 that she should be given a new name. But we don’t usually rename our kids when they grow up. They may choose to rename themselves, of course. For the moment I think Perl would like her name to stay Perl.

Now, I know what some of you are thinking: in anthropomorphizing Perl this way, Larry has gone completely off the deep end. That’s not possible–I started out by jumping off the deep end, and I haven’t noticed the water getting any shallower lately.

But in justification of my metaphor, let me just say that when I say “Perl” here, I’m not just talking about the language, but the entire culture. There are a lot of people who worked hard to raise Perl up to where she is today, and a bunch more people working hard to send her off to college. It’s the collective aspirations of those people that is the real personality of Perl.

When we first announced the Perl 6 effort back in 2000, we said it would be the community redesign of Perl. That continues to be the case today. It may look like I’m making all these arbitrary decisions as the language designer, but as with a teenager, you somehow end up making most of your decisions consistent with what they want. With what the Perl community wants, in this case.

If a teenager doesn’t want to listen to you, you can’t make ’em.

The fact is, Perl would be nothing without the people around her. Here’s a new acronym:

or if you like:

It really helps to have an extended family to raise a kid well. American culture has been somewhat reductionist in this respect, but a lot of other cultures around the world understand the importance of extended family. Maybe it’s just because Americans move around so much. But it’s a healthy trend that young people these days are manufacturing their own extended families. At the church I go to, we call it “Doing Life Together.” Here in the extended Perl family, we’re doing life together too.

We have people in our family like Uncle Chip and Aunt Audrey. There’s Cousin Allison, and Cousin Ingy, and Cousin Uri, and our very own Evil Brother Damian. I think Randal occasionally enjoys being the honorary black sheep of the family, as it were.

It all kind of reminds me of the Addams family. Hmm.

I watched The Addams Family a lot when I was young. Maybe you should call me Gomez, and call Gloria, Morticia. I must confess that I do love it when my wife speaks French. It gives me déjà vu all up and down my spine.

It’s okay for me to tell you that because I live in a fishbowl.

I’m not sure who gets to be Lurch. Or Thing. Anybody wanna volunteer? We’re always looking for volunteers in the Perl community. Don’t be scared. The Addams family can be a little scary, and so can the Perl family, but you’ll notice we’re also affectionate and accepting. In a ghoulish sort of way.

We could take this TV family metaphor a lot further, but fortunately for you I never watched the Partridge Family or The Brady Bunch or All in the Family or Father Knows Best. Those of you who were here before know I mostly watched The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

I also watched Combat, a World War II show. But I was kind of a gruesome little kid that way.

I like gruesome shows. Maybe that explains why I liked the Addams family. Hmm. I once sat on the lap of the Santa Claus at Sears and asked for all five toy machine guns listed in the Sears catalog that year. For some reason I didn’t get any of them. But I suppose my family loved me in spite of my faults. My role models in parenting obviously didn’t come from TV. Or maybe they did. You know, that would explain a lot about how my family turned out. In actual fact, the picture above is another self-portrait done by my daughter Geneva.

Anyway, I love my own family, even if they’re kind of peculiar at times. Last month we were staying at a Motel 6 in Medford, Oregon. Gloria kindly went off to fetch me a cup of coffee from the motel lobby, and then she came to this door and stood there for a while wondering how to pull the door open with her hands full. Then she realized that the door must have been designed by someone who thinks there should be only one obvious way to do it. Because, the fact is, you can either pull or push this door, despite what it says. I suggested we should start marking such pushmepullyu doors with a P*. We obviously need more globs in real life.

Anyway, back to my weird family–this summer as we were driving around, we had a great literary discussion about how Tolstoy debunks the Great Man theory of history in War and Peace. After discussing the far-too-heavily overloaded namespace in Russian novels and the almost complete absence of names in the Tale of Genji, we tried to decide if the Tale of Genji was the first novel or not, and decided that it was really the first soap opera. Of course, then there had to be a long discussion of what really was the first novel–Tale of Genji, Madame Bovary, or Sense and Sensibility. Then there’s the first romance, first mystery, first fantasy, first science fiction, first modern novel, etc. One interesting fact we noted was that the first in a genre almost always has to officially be some other genre too. For example, the Tale of Genji was written in the existing form of explication of some haiku. Transitional forms are important in biological evolution as well, as one species learns to become another species. That’s why we explicitly allow people to program babytalk in Perl. The only way to become smart is to be stupid first. Puts a new spin on the Great Man theory of history.

So then, as we were driving we saw a cloud formation resembling Thomas Jefferson, which led us to speculate on the Great Documents theory of history. “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” brought up the Great Slogans theory of history.

Back to Tolstoy: “Moscow didn’t burn because Napoleon decided to burn it. Moscow burned because it was made of wood.” Those of you who attended YAPC Chicago may recognize that as the Great Cow theory of history. Or maybe the lantern was really kicked over by a camel, and there was a coverup.

Anyway, back to the family again, presuming the house hasn’t burned down. They say that “A family is where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” Arguably, regardless of your viewpoint, many people have been, um, taken in by Perl culture.

Sorry. I have a low taste for taking people in with puns.

But hey, taking people in is good. And stray kitties.

Some families just naturally accumulate strays. My wife and I were both fortunate enough to grow up in families that took in strays as a matter of course. We have a number of honorary members of our own family. I think a good family tends to Borg people who need to be taken in. It’s a lot like the way Audrey hands out commit bits to Pugs left and right. It all one big happy hivemind. Er, I mean family.

Now, it’s all well and good to get people in the door, but that’s only the beginning of accessibility. Whenever you get someone new in the family, either by birth or by adoption, where do you go from there? You have to raise your kids somehow, and they’re all different. Raising different kids requires different approaches, just like computer problems do.

So, then, how do we raise a family according to the various computing paradigms?

Imperative programming is the Father Knows Best approach. It only works at all when Father does know best, which is not all that often. Often Mother knows “bester” than Father. Hi, Gloria. And a surprising amount of the time, it’s the kids who know “bestest.”

For some reason the Von Trapp family comes to mind. I guess you have to structure your family to make the Sound of Music together.

“Look, if you hit your sister, she will hit you back. Duh.”

Obviously anyone who doesn’t program their family functionally has a dysfunctional family. But what does it mean to have a functional family? “Being hit back is a function of whether you hit your sister.” On the surface, everything appears to be free of side effects. Certainly when I tell my kids to mind their manners it often seems to have no lasting effect. Really, though, it does, but in the typical family, there’s a lot of hidden state change wound in the call stack. We first learn lazy evaluation in the family.

“Don’t take the last piece of candy unless you really want it.” “Please define whether you really care, and exactly how much you care.” “I’m sure I care more than you do.”

That’s almost a direct quote from Heidi when she was young: “But I want it more than you do.”

Functional programming tends to merge into declarative programming in general. I married into a family where you have to declare whether you want the last piece of cheesecake, or you’re unlikely to get it.

Unfortunately, I grew up in more of a culture where it was everyone’s responsibility to let someone else have the cheesecake. This algorithm did not always terminate. After several rounds of, “No, you go ahead and take it, no you take it, no you take it …”

In the end, nobody was really sure who wanted the cheesecake. I guess you say it was a form of starvation. But when I married into my wife’s family I found out that I definitely wouldn’t get the cheesecake until I learned to predeclare.

Let’s see, inheritance is obviously important, or you wouldn’t have a family in the first place. On the other hand, the family is where culture is handed down in the form of design patterns. A good model of composition is important–a lot of the work of being a family consists of just trying to stay in one spot together. As a form of composition, we learn how to combine our traits constructively by playing various roles in the family. Sometimes those are fixed roles built at family composition time, and sometimes those are temporary roles that are mixed in at run time. Delegation is also important. I frequently delegate to my sons: “Lewis, take the trash out.”

That’s Design By Contract. “Keep your promises, young man!”

Metaprogramming. “Takes one to know one!”

Aspected-oriented programming comes up when we teach our kids to evaluate their methods in the broader context of society:

“Okay kid, now that you’ve passed your driver’s test, you still have to believe the stop signs, but when the speed limit sign says 65, what it really means is that you should try to keep it under 70. Or when you’re in Los Angeles, under 80.”

But I think the basic Perl paradigm is “Whatever-oriented programming.”

Your kid comes to you and says, “Can I borrow the car?”

You say: “May I borrow the car?”

They say: “Whatever …”

Should I push the door or pull it?

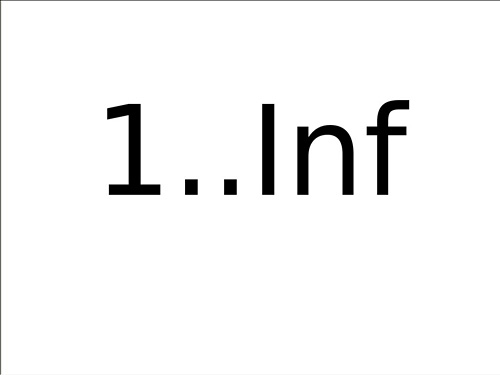

Actually, “whatever” is such an important concept that we built it into Perl 6. This is read, “from one to whatever.”

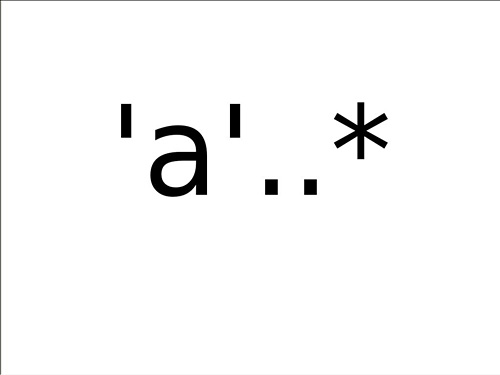

You might ask why we can’t just say “from one to infinity”:

The problem is that not all operators operate on numbers:

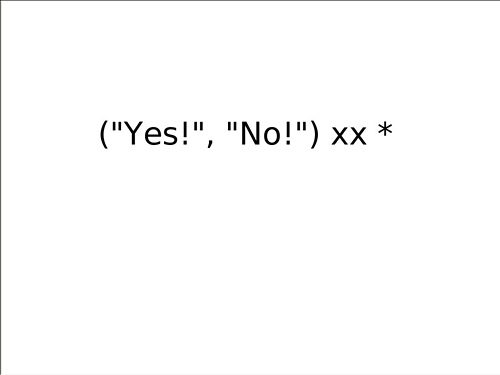

Not all operators are ranges. Here’s the sibling argument operator, which repeats the same words an arbitrary number of times:

Perl has always been about letting you care about the things you want to care about, while not caring about the things you don’t want to care about, or that maybe you’re not quite ready to care about yet. That’s how Perl achieves both its accessibility and its power. We’ve just baked more of that “who cares?” philosophy into Perl 6.

A couple of years ago, Tim O’Reilly asked me what great problem Perl 6 was being designed to solve. This question always just sat in my brain sideways because, apart from Perl 0, I have never thought of Perl as the solution to any one particular problem. If there’s a particular problem that Perl is trying to solve, it’s the basic fact that all programming languages suck. Sort of the concept of original sin, applied to programming languages.

As parents, to the extent that we can influence the design of our kids, we design our kids to be creative, not to solve a particular problem. About as close as we get to that is to hope the kid takes over the family business, and we all know how often that sort of coercion works.

No, instead, we design our kids to be ready to solve problems, by helping them learn to be creative, to be socially aware, to know how to use tools, and maybe even how to manufacture the tools for living when they’re missing. They should be prepared to do … whatever.

Trouble is, it takes a long time to make an adult, on the order of 20 years. Most insects don’t take 20 years to mature.

Apparently it takes you ten years to become an expert in being a kid, and then another ten years to become an expert in not being a kid. Some people never manage the second part at all, or have a strange idea of adulthood. Some people think that adulthood is when you just bake all your learning into hardware and don’t learn anything new ever again, except maybe a few baseball scores. That’s an oversimplified view of reality, much like building a hardwired Lisp machine. Neoteny is good in moderation. We have to be lifelong learners to really be adults, I think.

No, adulthood is really more about mature judgment. I think an adult is basically someone who knows when to care, and how to figure out when they should care when they don’t know offhand. A teenager is forever caring about things the parents think are unimportant, and not caring about things the parents think are important. Well, hopefully not forever. That’s the point. But it’s certainly a long process, with both kids and programming languages.

In computer science, it is said that premature optimization is the root of all evil. The same is true in the family. In parenting terms, you pick your battlefields, and learn not to care so much about secondary objectives. If you can’t modulate what you care about, you’re not really ready to parent a teenager. Teenagers have a way of finding your hot buttons and pushing them just to distract you from the important issues. So, don’t get distracted.

There are elements of the Perl community that like to push our collective hot buttons. Most of them go by the first name of Anonymous, because they don’t really want to stand up for their own opinions. The naysayers could even be right: we may certainly fail in what we’re trying to do with Perl 6, but I’d just like to point out that only those people who put their name behind their opinions are allowed to say “I told you so.” Anonymous cowards like the “told you so” part as long as it doesn’t include the “I.” Anonymous cowards don’t have an “I,” by definition.

Anyway, don’t let the teenage trolls distract you from the real issues.

As parents we’re setting up some minimum expectations for civilized behavior. Perl should have good manners by default.

Perl should be wary of strangers.

But Perl should be helpful to strangers.

While we’re working on their weaknesses, we also have to encourage our kids to develop where they have strengths, even if that makes them not like everyone else. It’s okay to be a little weird.

Every kid is different. At least, all my kids are really different. From each other, I mean. Well, and the other way too.

I guess my kids are all alike in one way. None of them is biddable. They’re all arguers and will happily debate the merits of any idea presented to them whether it needs further discussion or not. They’re certainly unlikely to simply wander off to the slaughter with any stranger that suggests it.

This is the natural result of letting them fight as siblings, with supervision. It’s inevitable that siblings will squabble. Your job as parent is to make sure they fight fair. It helps a lot if the parents have already learned how to fight fair. What I mean by fight fair is that you fight about what you’re fighting about–you don’t fight the other person. If you find yourself dragging all sorts of old baggage into an argument, then you’re fighting the person, you’re not fighting about something anymore. Nothing makes me happier as a parent than to hear one of my kids make a logical argument at the same time as they’re completely pissed off.

If you teach your kids to argue effectively, they’ll be resistant to peer pressure. You can’t be too careful here. There are a lotta computer languages out there doing drugs. As a parent, you don’t get into a barricade situation and isolate your kids from the outside world forever. Moving out and building other relationships is a natural process, but it needs some supervision.

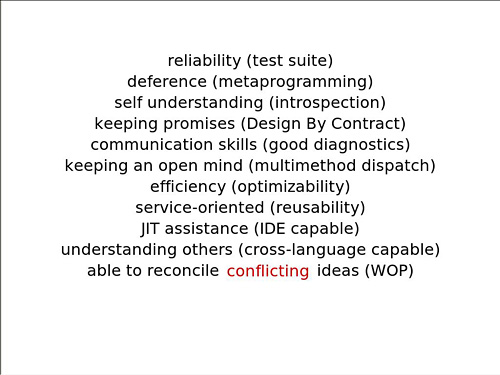

Perl is learning to care deeply about things like:

This final point is crucial, if you want to understand the state of Perl today. Perl 6 is all about reconciling the supposedly irreconcilable.

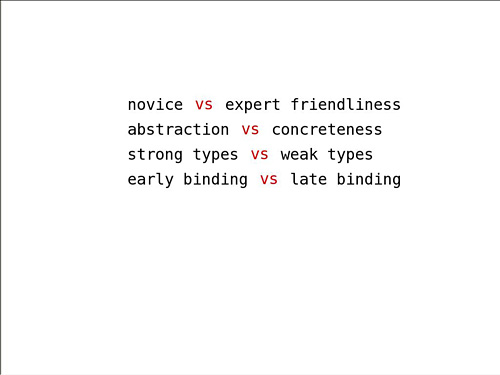

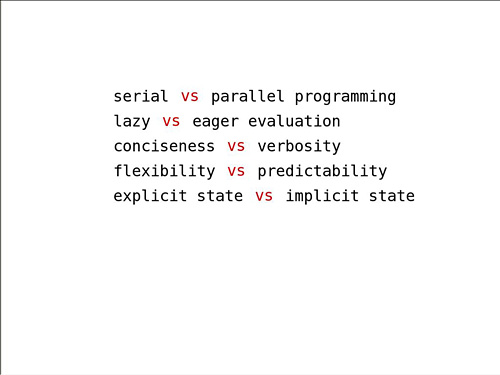

Reconciling the seemingly irreconcilable is part of why Perl 6 taking so long. We want to understand the various tensions that have surfaced as people have tried to use and extend Perl 5. In fact, just as Perl 1 was an attempt to digest Unix Culture down into something more coherent, you can view Perl 6 as an attempt to digest CPAN down into something more coherent. Here are some of the irreconcilables we run into when we do that:

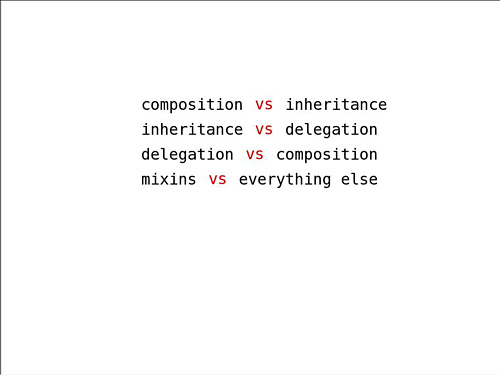

OO brings us a world of choices:

Do we even have classes at all?

And if we do, how do they inherit and dispatch?

Is our type system more general than our class system?

Plus a grab bag of other issues:

And finally, the biggie:

Reconciling these known conflicts is all well and good, but our goal as a parent must be a bit larger than that.

Just as a child that leaves the house today will face unpredictable challenges tomorrow, the programming languages of the future will have to reconcile not only the conflicting ideas we know about today, but also the conflicting ideas that we haven’t even thought of yet.

We don’t know how to do that. Nobody knows how to do that, because nobody is smart enough. Some people pretend to be smart enough. That’s not something I care about.

Nevertheless, a lot of smart people are really excited about Perl 6 because, as we go about teaching Perl how to reconcile the current crop of irreconcilables, we’re also hoping to teach Perl strategies for how to cope with future irreconcilables. It’s our vision that Perl can learn to care about what future generations will care about, and not to care about what they don’t care about.

That’s pretty abstruse, I’ll admit. Future-proofing your children is hard. Some of us get excited by the long-term potential of our kids. But it’s also exciting when you see their day-to-day progress. And we’ve make a lot of progress recently.

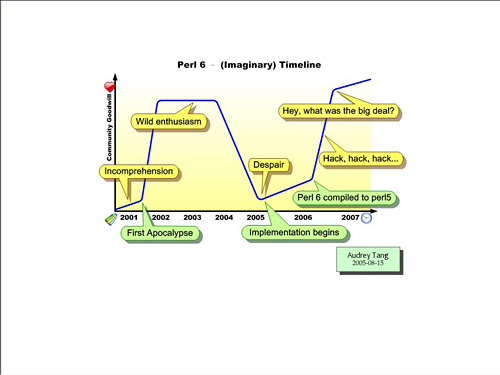

In terms of Audrey’s Perl 6 timeline, we’re right at that spot where it says “hack, hack, hack.” In a year or so we’ll be up here saying, “What’s the big deal?”

This is the year that Perl 6 will finally be bootstrapped in Perl 6, one way or another. Actually, make that one way and another. There are several approaches being pursued currently, in a kind of flooding algorithm. One or another of those approaches is bound to work eventually.

Now, anyone who has been following along at home knows that we never, ever promise a delivery date for Perl 6. Nevertheless, I can point out that many of us hope to have most of a Perl 6 parser written in Perl 6 by this Christmas. The only big question is which VM it will compile down to first. There’s a bit of a friendly race between the different implementations, but that’s healthy, since they’re all aiming to support the same language.

So one of the exciting things that happened very recently is that the Pugs test suite was freed from its Haskell implementation and made available for all the other implementations to test against. There are already roughly 12,000 tests in the test suite, with more coming every day. The Haskell implementation is, of course, the furthest along in terms of passing tests, but the other approaches are already starting to pass the various basic sanity tests, and as many of you know, getting the first test to pass is already a large part of the work.

So the plan is for Perl 6 to run consistently on a number of platforms. We suspect that eventually the Parrot platform is likely to be the most efficient way to run Perl 6, and may well be the best way to achieve interoperability with other dynamic languages, especially if Parrot can be embedded whole in other platforms.

But the other virtual machines out there each have their own advantages. The Haskell implementation may well turn out to be the most acceptable to academia, and the best reference implementation for semantics, since Haskell is so picky. JavaScript is already ubiquitous in the browsers. There are various ideas for how to host Perl 6 on top of other VMs as well. Whatever.

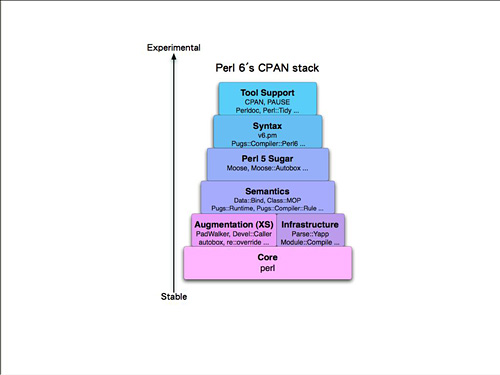

But the VM that works the best for Perl right now is, in fact, Perl 5. We’ve already bootstrapped much of a Perl 5 compiler for Perl 6. Here’s a picture of the approach of layering Perl 6 on Perl 5.

Here in the middle we have the Great Moose theory of history.

Other stuff that’s going on:

In addition to lots of testing and documentation projects, I’m very happy that Sage La Torra is working on a P5-to-P6 translator for the Google Summer of Code. Soon we’ll be able to take Perl 5 code, translate it to Perl 6, and then translate it back to Perl 5 to see how well we did.

Another bootstrapping approach is to take our current Haskell codebase and translate to Perl 6. That could be very important long term in keeping all the various implementations in sync.

There are many, many other exciting things going on all the time. Hang out on the mailing lists and on the IRC channels to find out more.

If you care.

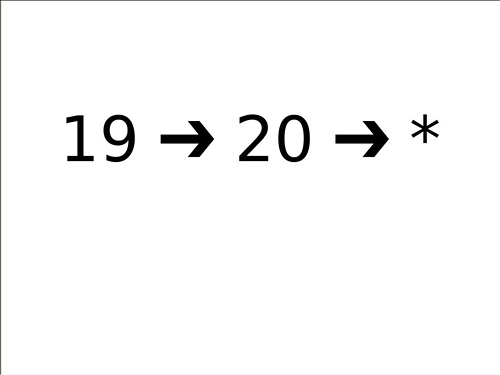

Perl is growing up, but she’s doing so in a healthy way, I think. Those of us who are parents tend to try to discourage our kids from getting married too young, because we know how much people change around their twentieth year. Around the age of 19 or 20 is when we start that last major rewiring of our brains to become adults. This year, Perl will be 19 going on 20. She’s due for a brain rewiring.

In previous years, Perl was just trying to act grownup by ignoring her past. This year, I’m happy to report that instead of just trying to act grownup, Perl is going back and reintegrating her personality to include the positive aspects of childhood and adolescence. I don’t know where Perl will go in the next ten or twenty years. It’s my job to say, “I don’t care anymore,” and kick her out of the house. She’s a big girl now, and she’s becoming graceful and smart and wise, and she can just decide her future for herself.

Whatever. Thanks for listening, and for learning to care, and for learning to not care. Have a great conference! I don’t care how!

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub