Colonizing the Lacuna Expanse with Perl

Perl productivity has suffered this month with JT Smith’s announcement of The Lacuna Expanse, a web-based space empire strategy game. As with most of Smith’s projects, TLE uses Perl extensively. Perl.com recently conducted an email interview to explore the world behind the game world.

You’re a successful serial entrepreneur. How’d you get into Perl?

I started my professional career as an Engineer at a TV station. As the web started to get popular in the early 90’s I started picking up web development for the TV station, and then eventually went to work at an ISP as a web developer and system administrator. That’s when I first picked up Perl, as it was already installed on the DEC Unix boxes they were running. I realized how easy it was to use it to automate a lot of my job (deploying sites, running backups, collecting statistics, munging logs), and a little web stuff here and there too (processing forms, writing message boards and polls). Since then I’ve used several other languages (PHP, Java, and Ruby mostly), but I always come back to Perl because it solves the most problems for me with the littlest amount of fuss.

What’s your business background?

I have no formal business training, but I’ve worked at lots of companies big and small, and either started or helped start about a dozen companies now, four of which I still own. So I’ve really picked up a lot of my business expertise through trial and error, and through watching the successes and failures of other businesses.

Some people follow sports and can quote you the scores and statistics of their favorite teams. For me, I prefer to watch businesses and business leaders. And when I read for entertainment, it’s almost never fiction. Instead I like to read about things that can give me ideas to apply. For instance, I just finished “The Viral Loop,” which covers viral marketing history from Tupperware through Facebook. I know all this sounds pretty nerdy/geeky/dorky, but so be it.

How did you decide to do a browser-based game?

Actually long before I built WebGUI, in the CGI era, I built one of the very first web-based RPG systems. It was called Survival of the Fittest. And back about that time I had the idea for The Lacuna Expanse (it was called Star Games back then), but the technology wasn’t there to pull off what I really wanted to do.

Then last year (released July 14, 2009) I built a new business called The Game Crafter. It is a web to print company, where people design board games and card games using their web browser (plus some offline image editing) and when they’re done, they can order a copy for themselves, or put it up in our online store to sell to potential customers. It’s sort of like Lulu or CafePress, but for traditional board and card games. Here we are just over a year later and that business has really taken off, with over 1,500 people making custom games, and 70% of customers returning for more than one order. I should mention that TGC is built with 100% pure Perl as well.

About the time that The Game Crafter launched, another business that I had created four years earlier started actually making some good money. That business is CMS Matrix, and yes it’s 100% pure Perl as well.

After about 6 months of seeing how well The Game Crafter and CMS Matrix were doing, and knowing that I had a solid team in place to keep WebGUI marching forward, my business partners and I decided we should take a chance with yet another business. But this time we decided we wanted to tackle something much more ambitious and risky.

One of my business partners reminded me of the Star Games idea. And there’s hardly anything more risky than making a video game. It has a large up front cost of both time and money, and video games pretty much either make a lot of money, or none at all. There’s not much of a middle of the road. With Star Games as our foundation, we started designing game mechanics. We didn’t want to build yet another war game (too many of those) so we settled on espionage as our conflict mechanism. And until WoW and The Sims came around, there was one game that dominated the landscape as far as revenue goes, SimCity. So we knew the game had to have a city building element. And everything else was stuff we either made up, or ideas we borrowed from our favorite games.

What did you have to invent and what did you reuse?

Luckily CPAN came to the rescue as it has on basically every Perl project I’ve ever tackled. So I was able to not have to reinvent the wheel on basically any foundational level. Here’s the list of Perl modules I used:

- Data::Validate::Email

- Text::CSV_XS

- Log::Log4perl

- UUID::Tiny

- DateTime::Format::MySQL

- DBIx::Class::TimeStamp

- JSON::XS

- JSON

- Config::JSON

- Starman

- JSON::RPC::Dispatcher

- Log::Any::Adapter

- Log::Any::Adapter::Log4perl

- String::Random

- List::Util::WeightedChoice

- List::Util

- List::MoreUtils

- DateTime

- Regexp::Common

- Pod::Simple::HTML

- File::Copy

- DateTime::Format::Duration

- XML::FeedPP

- SOAP::Amazon::S3

- DBD::mysql

- DBIx::Class

- JSON::Any

- DBIx::Class::InflateColumn::Serializer

- DBIx::Class::DynamicSubclass

- Memcached::libmemcached

- Server::Starter

- IO::Socket::SSL

- Net::Server::SS::PreFork

- Email::Stuff

- Facebook::Graph

- File::Path

- namespace::autoclean

- Clone

- Plack::Middleware::CrossOrigin

- Net::Amazon::S3

When I first started development I was convinced that to be massively parallel I was going to have to go with an async server like Coro or POE, and a NoSQL database.

I quickly realized that writing this system to be completely async was going to be a nightmare that would take more than double the time. Part of the problem was that while I was familiar with developing async applications, I had only done it on a small scale in the past. The other problem was that I kept running into modules I wanted to use that weren’t async compatible. Ultimately I ditched the idea of going async within the first month.

Unfortunately I wasn’t so quick to ditch the idea of NoSQL. I started with MongoDB and CouchDB, but had trouble compiling them with the Perl bindings. I planned on hosting on Amazon at that point, so I decided to give SimpleDB a go. The downside there was that there were no decent Perl bindings for SimpleDB, that weren’t entirely bare bones. So with that I created SimpleDB::Class (based loosely on DBIx::Class). The module works great. Unfortunately SimpleDB doesn’t. It’s super slow. So four months into development, with a whimper, I had to ditch my beloved SimpleDB::Class module. I’m glad I did. Development has been much faster and easier since then, and a good amount of thanks goes to DBIx::Class for that.

WWW::Facebook::API has been largely abandoned by its author. He told me he doesn’t have time to maintain it anymore. And I was having a hard time getting it to work anyway. As luck would have it Facebook just announced their Graph API, so I decided to take on that project, and build a Perl wrapper around it. And Facebook::Graph was born. This enabled me to allow Facebook users to Single Sign On into the web site, the game, and also interact with their accounts.

About the only other non-game piece that I had to invent of any consequence was JSON::RPC::Dispatcher, which is a Plack enabled web service generator. There are some other JSON-RPC modules on CPAN, but for one reason or another I found them all completely insufficient. Mostly because of one or more of four reasons:

- It didn’t support JSON-RPC 2.0.

- Its documentation was so poor that I couldn’t make it work.

- It made me write a ton of code to simply expose a web service.

- It wasn’t PSGI/Plack compatible.

With JSON::RPC::Dispatcher, I can expose object-oriented code as web services with a single line of code.

I’m not very happy with the Perl modules that are out there for S3 right now. Right now we’re using a combination of SOAP::Amazon::S3, and Net::Amazon::S3, and neither are particularly good, at least for our purposes. They both work, but only for fairly basic purposes. Sometime in the near future I’ll either take on a massive overhaul of one of those modules, or write my own from scratch. Which remains to be seen depending on how open the authors of those modules are to patches.

What did you need from SimpleDB besides more speed?

What I was hoping I’d get out of SimpleDB was three things: massive parallelism, hierarchical data structure storage, and schema-less storage to make my upgrade path easier. It provided all of those things.

What I hadn’t anticipated was all the limitations it would place on me. Speed was just the nail in the coffin. It also puts pretty harsh limits on the amount of data per record, the amount of data returned per result set, and the complexity of queries. In addition, like most NoSQL databases it’s eventually consistent, which provides its own host of problems. I had worked my way around pretty much all that, and then finally hit the performance bottleneck.

At that point I knew I had to make a change, because I wouldn’t be able to make up the difference in parallelism. For example, in order to process functions on a building, I would need planet data, and empire data in addition to the building data. But I wouldn’t know what empire or planet to fetch until I fetched the building, which meant I’d have to do serial processing. And I couldn’t cache all the data for the empire and the planet in the building (or vice versa) because of the limits on the amount of data allowed to be stored per record. My two options were: 1) Bring everything forward into memcached, which has its own problems because I’d have to create an indexing system; 2) Move to a relational database.

When did you start using Plack?

I first heard about Plack late last year when one of the contributors to WebGUI did an initial test implementation (PlebGUI) to see if we could use it in WebGUI. After seeing how cool it was I knew that WebGUI 8 had to have it, and all my future projects would also use it.

What’s been the biggest benefit for you?

The benefits are so huge that they are hard to enumerate, so I’ll pick the top 3 or 4. For the Lacuna Expanse, the main benefit was ease of development. There were no longer any hoops to jump through (the mod_perl landscape can be tricky to navigate). Sometime later Starman came out and that gave me an instant boost to performance, which was also nice. For WebGUI the middleware components were instrumental. They allowed us to eliminate a lot of code we previously had to write ourselves rather than using shared libraries. In addition, just switching from mod_perl 2 to Starman (no other changes), gave us a 300% performance boost.

You seem to be comfortable using a lot of new technologies with a reasonable amount of traffic. How do you see the risks and the rewards?

First and foremost Miyagawa, who wrote Starman and much of Plack, is my personal Perl hero. It seems like everything he writes is absolute gold. So the fact that he wrote it adds some confidence.

But you’re right, in general I’m not averse to using new technologies. The problem with “tried and true” is that it’s often “old and stale”. So from my perspective, there are just as many risks choosing proven technologies as there are new ones. That doesn’t mean you can blindly adopt new technologies, but you should be on the lookout for them. The rest of the risk/reward decision comes from my business experience: Change is inevitable. If you try something and it doesn’t work out, so what? Sure it’s going to cost you some time/money, but maintaining antiquated systems costs a lot of money too. These days the pace of technology moves too quickly to rest on tried and true alone.

Are you comfortable with the risk that you’ll run into maturity problems and can patch them or work around them, or do you think that despite their relative youth, they’re very capable for your purposes?

Here’s the thing. When you’re running a technology based business, the only thing you can plan for is that things will change.

Let’s use scalability as an example. If you try to build a system that will infinitely scale before you have any users then you’ll spend a lot of time and money on something that may never get any users. At the same time, if you put no time into planning for some amount of scaling, then you won’t have enough breathing room to keep your users happy while you refactor.

Likewise you can’t anticipate all the features you’ll ever need, because user’s desires are hard to predict. And because of this, at some point you’ll likely make a fundamental flaw in your architecture that will require at least a partial rewrite of your software. This is very much a business decision. Most developers I know cry when I say that, because most believe that it’s both possible and desirable to reach design/implementation nirvana. The fact is that users don’t care if your APIs are perfect. They care if your software does what they need it to do. From a business perspective it’s often more profitable to build something quickly and then continually refactor or even rewrite it to match demand.

I say all of this to make the point that if a particular new technology doesn’t work out like we expected it to, then we’ll simply replace it in the next iteration. If you go into the project with that mentality you’ll likely be more successful.

What’s the basic architecture of The Lacuna Expanse?

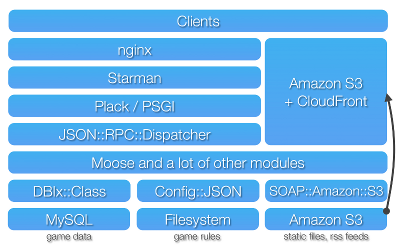

The basic software architecture looks like:

Basically per server configurable game rules go into various Config::JSON config files. DBIx::Class and MySQL handle all of the game data storage and querying. Memcached sits off to the side and handles lock contentions, limit contentions, session management, and other server coordination communication. Unfortunately, not much can actually be cached due to the dynamic nature of the game, unless I was willing to cache basically everything, which I’m not. And all the static stuff, like images, JavaScript, and CSS files get served up from CloudFront. We also push our RSS feeds and other semi-static game content out to S3.

Basically per server configurable game rules go into various Config::JSON config files. DBIx::Class and MySQL handle all of the game data storage and querying. Memcached sits off to the side and handles lock contentions, limit contentions, session management, and other server coordination communication. Unfortunately, not much can actually be cached due to the dynamic nature of the game, unless I was willing to cache basically everything, which I’m not. And all the static stuff, like images, JavaScript, and CSS files get served up from CloudFront. We also push our RSS feeds and other semi-static game content out to S3.

The game engine itself is basically an MVC setup built with Moose. DBIx::Class and Config::JSON act as the model. Some custom Moose objects tied to Memcached::libmemcached act as the controller handling session management, privileges, etc. And JSON::RPC::Dispatcher acts as the view.

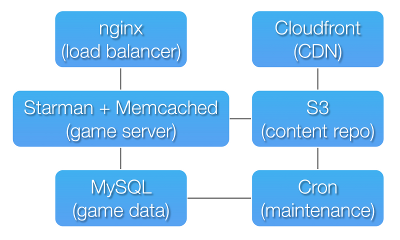

The basic server architecture looks like this:

Any of the server nodes can be set up in either a clustered or load balanced formation to handle traffic growth.

Any of the server nodes can be set up in either a clustered or load balanced formation to handle traffic growth.

And finally we use Github as our deployment system. We use its service hooks feature to trigger pushing new content to S3/Cloudfront and code to the game servers.

How many people are working on this?

Six, plus a bunch of play testers. One artist named Ryan Knope; plus a part time helper, Keegan Runde, who is the son of one of the other developers. One on iPhone development, named Kevin Runde. Two on Web Client development John Rozeske and Graham Knop. Myself on server development. And myself and my business partner Jamie Vrbsky on game mechanics development.

We started development in January 2010, and officially launched the game on October 4, 2010. Now that we’ve launched, I’ve brought in one of my other business partners, Tavis Parker, to help out with marketing the game. And we’re still pushing forward on new releases. We hope to have our first expansion for the game, called “Enemy Within”, out sometime in Q1 2011.

How do you manage your development process?

We’re very loose on management.

We basically have a strategy meeting every 2 weeks at a local pub, where we discuss whatever needs to be discussed in person. Beyond that we have a play testers mailing list, a developers mailing list, and a defect tracking system that we use internally. And other than that communicate through Skype and email.

We manage all of our code and content through various public and private github repositories. We share documents and art mockups using Dropbox.

I publish all the JSON-RPC APIs out using POD (nicely formatted using Pod::Simple::HTML) to our play testers server, which is what the client guys develop against. And then ultimately once vetted and implemented by our client guys, the APIs are pushed out to the public server here at http://us1.lacunaexpanse.com/api/.

What little project management and coordination we need is handled by me emailing back and forth.

How often are your releases? What’s the breakdown between bugfixes and new development?

For the Lacuna Expanse we’re doing releases about 4 or 5 times a week. 1 or 2 of them contain some new features, and the rest are bug fixes. However, TLE is very new. In the beginning it’s very important to react quickly to your users needs because they often find bugs you didn’t, or have feature ideas that are almost fundamental after you hear them, but you never thought of them during the development process. By the end of the year our development cycle will slow down quite a bit, probably to once per week.

For WebGUI we release approximately once per week, and those releases are primarily bug fixes. We generally do about 2 major releases per year that are primarily new features.

For The Game Crafter we’ve stopped doing releases, except for the occasional bug fix because we’re coming into the holiday season. Starting in January we’re going to get going on a complete rewrite (about a six month process), which will quadruple our feature set, give us about a 700% performance gain, and allow us to scale with the growing demands our customers are placing on us.

Recruit existing Perl developers in your area, work with people you’ve worked with before, or hire good people and train them?

All of the above. When you’re looking to hire someone you should hire the best person you can afford to hire. In our case this means we’ve decided to design our businesses around telecommuting. We still maintain a small office, and still hire locally when we can, and we even provide incentives for our employees to move to Madison if they so desire, but we never throw out a resume based upon location, what schools they attended, or whether or not they’ve happened to work with the particular modules and technologies we’re working with.

I keep an eye on one of the alliances in the game populated by a lot of well- known Perl developers, and they seem to be pushing the limits of the public API. I know you made this API public for a reason (and increased the call limit)–but do you foresee an endgame where the best client automation wins, or do you expect that the game strategy will be malleable such that clever players have an edge over automation?

Automation has its advantages certainly. It’s great for getting the mundane crap out of the way.

Most games spend a lot of time and effort doing everything they can to prevent people from automating their game. The trouble is that you end up wasting a lot of effort trying to stop smart people from being smart. If they really want to automate something they will find a way around your restrictions. It’s a never ending arms race.

In our case we decided to embrace these people. Better and better tools will come along and ultimately that means these people are adding features to our game that we didn’t have to write. Because eventually the tools will get simple enough that your average Joe can run them.

As far as the game is concerned it doesn’t make a bit of difference that you can use a tool to push a button in the game, rather than pushing the button yourself. You still have to follow the same rules. It takes a certain amount of time to happen, you have to spend a certain amount of resources, etc. When it comes right down to it, someone still has to make all of the important decisions, and that’s not likely going to be a tool anytime soon. You have to decide what buildings to upgrade in what order, what ships to build, who to attack, how to defend, etc. And once the next expansion comes out, you’ll have to work with your team mates to build a space station, enact laws, and defend your federation of planets. It will be very much a social endeavor.

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub